On This Page:ToggleWhat is Thematic Analysis?TypesSix StepsPitfalls to AvoidReducing BiasAdvantagesDisadvantagesReading List

On This Page:Toggle

On This Page:

What is Thematic Analysis?

Thematic analysis is aqualitative research methodused to identify, analyze, and interpret patterns of shared meaning (themes) within a given data set, which can be in the form ofinterviews,focus group discussions, surveys, or other textual data.

Thematic analysis is a useful method for research seeking to understand people’s views, opinions, knowledge, experiences, or values from qualitative data.

This method is widely used in various fields, including psychology, sociology, and health sciences.

Thematic analysis minimally organizes and describes a data set in rich detail. Often, though, it goes further than this and interprets aspects of the research topic.

Key aspects of thematic analysis include:

Types

Many researchers mistakenly treat thematic analysis (TA) as a single, homogenous method. However, as Braun and Clarke emphasize, TA is more accurately described as an “umbrella term” encompassing a diverse family of approaches.

These approaches differ significantly in terms of their procedure and underlying philosophies regarding the nature of knowledge and the role of the researcher.

It’s important to note that the types of thematic analysis are not mutually exclusive, and researchers may adopt elements from different approaches depending on their research questions, goals, and epistemological stance.

1. Coding Reliability Thematic Analysis

Coding reliability, frequently employed in the US, leans towards apositivist philosophy. It prioritizes objectivity and replicability, often using predetermined themes or codes.

Coding reliability TA emphasizes usingcoding techniquesto achieve reliable and accurate data coding, which reflects (post)positivist research values.

This approach emphasizes the reliability and replicability of the coding process. It involves multiple coders independently coding the data using apredetermined codebook.

The goal is to achieve a high level of agreement among the coders, which is often measured using inter-rater reliability metrics.

This approach often involves a coding frame or codebook determined in advance or generated after familiarization with the data.

In this type of TA, two or more researchers apply a fixed coding frame to the data, ideally working separately.

Some researchers even suggest that some coders should be unaware of the research question or area of study to prevent bias in the coding process.

Statistical tests are used to assess the level of agreement between coders, or the reliability of coding. Any differences in coding between researchers are resolved through consensus.

This approach is more suitable for research questions that require a more structured and reliable coding process, such as in content analysis or when comparing themes across different data sets.

2. Reflexive Thematic Analysis

Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis is an approach to qualitative data analysis that emphasizes researchers’ active role in knowledge construction.

It involves identifying patterns across data, acknowledging how researchers’ perspectives shape theme development, and critically reflecting on the analysis process throughout the study.

It acknowledges that the researcher’s subjectivity, theoretical assumptions, and interpretative framework shape the identification and interpretation of themes.

In reflexive TA, analysis starts with coding after data familiarization. Unlike other TA approaches, there is no codebook or coding frame. Instead, researchers develop codes as they work through the data.

As their understanding grows, codes can change to reflect new insights—for example, they might be renamed, combined with other codes, split into multiple codes, or have their boundaries redrawn.

If multiple researchers are involved, differences in coding are explored to enhance understanding, not to reach a consensus. The finalized coding is always open to new insights and coding.

Reflexive thematic analysis involves a more organic and iterative process of coding and theme development. The researcher continuously reflects on their role in the research process and how their own experiences and perspectives might influence the analysis.

This approach is particularly useful for exploratory research questions and when the researcher aims to provide a rich and nuanced interpretation of the data.

3. Codebook Thematic Analysis

Codebook TA, such as template, framework, and matrix analysis, combines coding reliability and reflexive elements.

Codebook TA, while employing structured coding methods like those used in coding reliability TA, generally prioritizes qualitative research values, such as reflexivity.

In this approach, the researcher develops acodebookbased on their initial engagement with the data. The codebook contains a list of codes, their definitions, and examples from the data.

The codebook is then used to systematically code the entire data set. This approach allows for a more detailed and nuanced analysis of the data, as the codebook can be refined and expanded throughout the coding process.

It is particularly useful when the research aims to provide a comprehensive description of the data set.

Codebook TA is often chosen for pragmatic reasons in applied research, particularly when there are predetermined information needs, strict deadlines, and large teams with varying levels of qualitative research experience

The use of a codebook in this context helps to map the developing analysis, which is thought to improve teamwork, efficiency, and the speed of output delivery.

Why coding reliability doesn’t fit with reflexive TA:Using coding reliability measures in reflexive TA represents an attempt to quantify and control for subjectivity in a research approach that explicitly values the researcher’s unique contribution to knowledge construction.Braun and Clarke argue that such attempts to bridge the “divide” between positivist and qualitative research ultimately undermine the integrity and richness of the reflexive TA approach.The emphasis on coding consistency can stifle the very reflexivity that reflexive TA encourages.

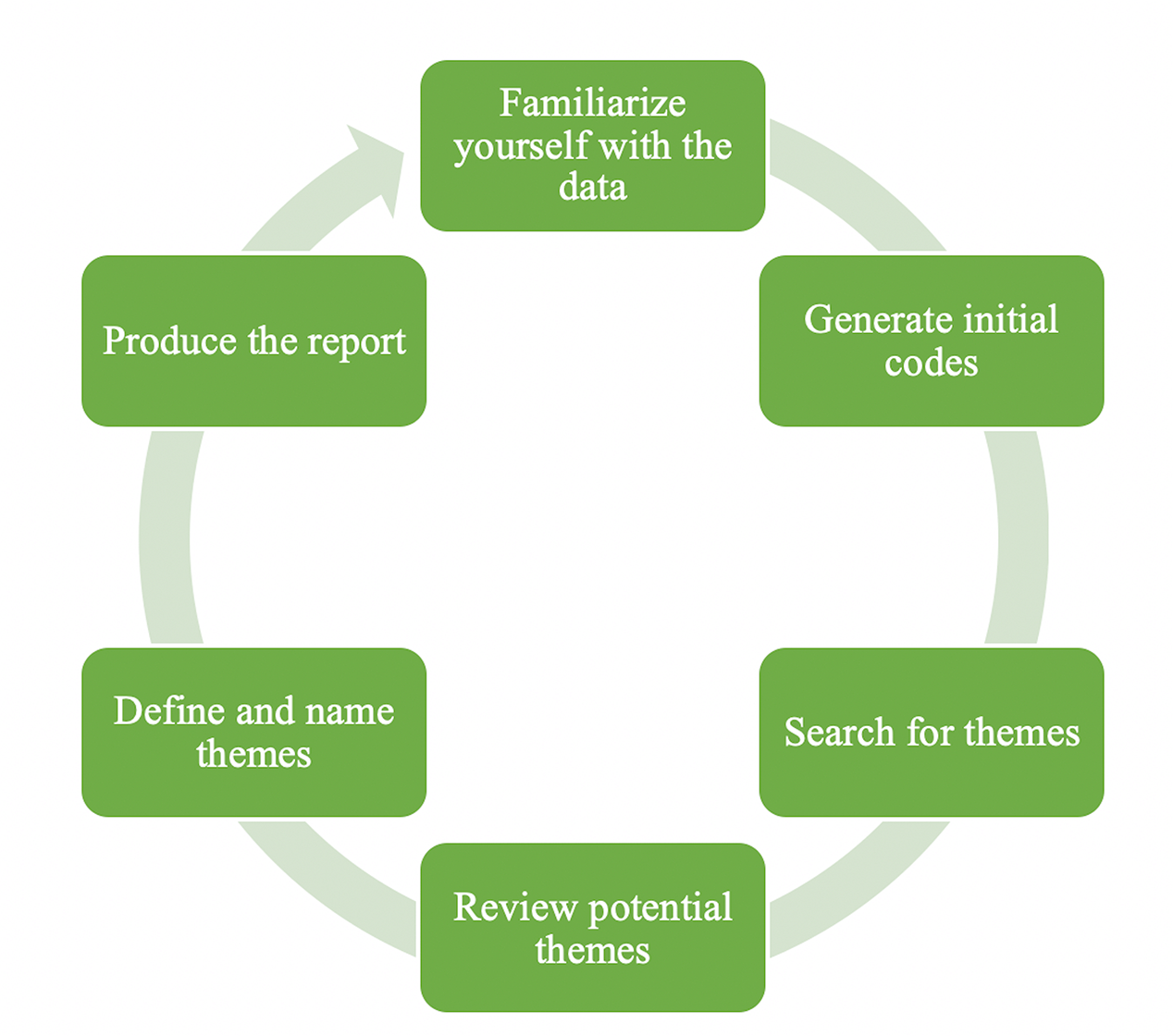

Six Phases Of Reflective Thematic Analysis

This means that researchers might revisit earlier phases as their understanding of the data evolves, constantly refining their analysis.

For instance, during the reviewing and developing themes phase, researchers may realize that their initial codes don’t effectively capture the nuances of the data and might need to return to the coding phase.

This back-and-forth movement continues throughout the analysis, ensuring a thorough and evolving understanding of the data.

Here’s a breakdown of the six phases:

The continuous cycle of Thematic Analysis (adapted from Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2012)

Step 1: Familiarization With the Data

Familiarization is crucial, as it helps researchers figure out the type (and number) of themes that might emerge from the data.

You should read through the entire data set at least once, and possibly multiple times, until you feel intimately familiar with its content.

This deep engagement with the data sets the stage for the subsequent steps of thematic analysis, where the researcher will systematically code and analyze the data to identify and interpret the central themes.

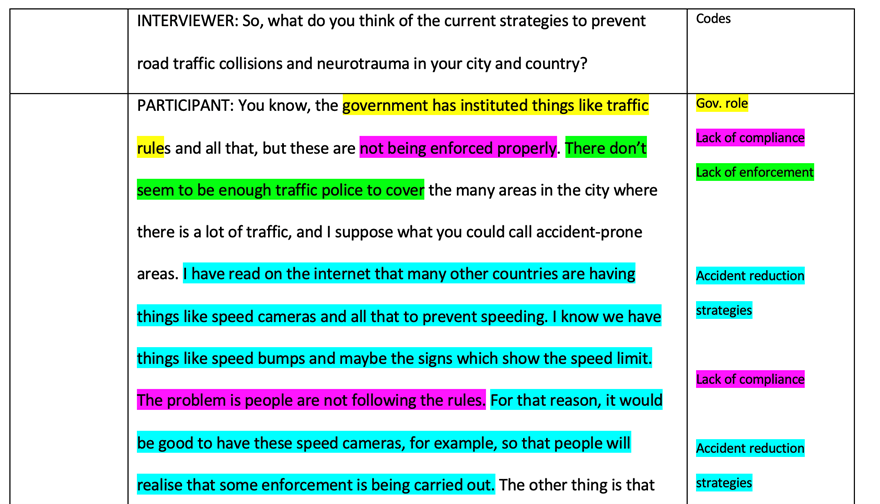

Step 2: Generating Initial Codes

Codes are concise labels or descriptions assigned to segments of the data that capture a specific feature or meaning relevant to the research question.

Research question(s)and codingBraun and Clarke argue that the research question should be at the forefront of the researcher’s mind as they engage with the data, helping them focus their attention on what is relevant and meaningful.The research question is not set in stone; it can, and often should, evolve throughout the analysis.Braun and Clarke encourage a flexible and iterative dance between the research question and the coding process in reflexive thematic analysis.They advocate for a dynamic interplay where the research question guides the analysis while remaining open to refinement and even transformation based on the insights gleaned from deep engagement with the data.The coding process, with its close engagement with the data, can reveal new insights, nuances, and avenues for exploration, potentially leading to a reframing or narrowing of the initial research question.

Research question(s)and coding

Theprocess of qualitative codinghelps the researcher organize and reduce the data into manageable chunks, making it easier to identify patterns and themes relevant to the research question.

Think of it this way:If your analysis is a house, themes are the walls and roof, while codes are the individual bricks and tiles.

Coding is an iterative process, with researchers refining and revising their codes as their understanding of the data evolves.

The ultimate goal is to develop a coherent and meaningful coding scheme that captures the richness and complexity of the participants’ experiences and helps answer the research question(s).

Qualitative data analysis software, such as NVivo can streamline the coding process, help you organize your data, and facilitate searching for patterns.

Example:Instead of manually writing codes on note cards or in separate documents, you can use software to directly tag and categorize segments of text within your data. This allows for easy retrieval and comparison of coded extracts later in the analysis

However, while software can assist with tasks like organizing codes and visually representing relationships, the researcher maintains responsibility for interpreting the data, defining themes, and making analytical decisions.

Codes usually are attached to ‘chunks’ of varying size-words, phrases, sentences, or whole paragraphs. They can take the form of a straightforward descriptive label or a more complex interpretive one (e.g. metaphor).

Decide On Your Coding Approach

Instead of chasingdata saturation, Clarke advocates for aiming for “theoretical sufficiency“. This means coding data until you have enough evidence to confidently and convincingly support your interpretations and answer your research question.

Do A First Round Of Coding

After generating your first code, compare each new data extract to see if an existing code applies or if a new one is needed.

Avoid getting bogged down in trying to create the “perfect” set of codes from the outset. Embrace the iterative nature of coding, refining, and adjusting as needed

When grappling with the decision of whether to code a particular data segment, Braun and Clarke advocate for an inclusive approach, particularly in the initial stages of analysis.

They emphasize that it’s easier to discard codes later than to revisit the entire dataset for recording.

Coding can be done at two levels of meaning:

Semantic codes provide a descriptive snapshot of the data, while latent codes offer a more interpretive and deeper understanding of the underlying meanings and assumptions present.

The decision of whether to use semantic or latent codes, or a mix of both, depends on the research question, the specific data, and the theoretical orientation of the researcher.

Latent coding requires more experience and theoretical knowledge than semantic coding.

Most codes will be a mix of descriptive and conceptual. Novice coders tend to generate more descriptive codes initially, developing more conceptual approaches with experience.

Both types of codes are valuable in thematic analysis and contribute to a more comprehensive and insightful analysis of qualitative data.

Evolution of codes:

Braun and Clarke underscore that in reflexive TA, codes are not static categories but rather evolving tools that the researcher actively shapes and reshapes in response to the emerging insights from the data.

Don’t be afraid to revisit and adjust your codes —this is a sign of thoughtful engagement, not failure.

Braun and Clark highlight how codes might be:

This step ends when:

You have enough codes to capture the data’s diversity and patterns of meaning, with most codes appearing across multiple data items.

The number of codes you generate will depend on your topic, data set, and coding precision.

Step 3: Generating Initial Themes

Generating initial provisional (candidate) themes begins after all data has been initially coded and collated, resulting in a comprehensive list of codes identified across the data set.

This step involves shifting from the specific, granular codes to a broader, more conceptual level of analysis.

What is the difference between a theme and a code?A code is attached to a segment of data (your “coding chunk”) that is potentially relevant to your research questionThemes are built from codes, meaning they’re more abstract and interpretive.Codes capture a single idea or observation, while a theme pulls together multiple codes to create a broader, more nuanced understanding of the data.Think of codes as the building blocks, and themes as the structure you create using those blocks.

What is the difference between a theme and a code?

Phase 3 of thematic analysis is about actively “generating initial themes” rather than passively “searching for themes.” The distinction highlights that researchers don’t just uncover pre-existing themes hidden within the data.

Thematic analysis is not about “discovering” themes that already exist in the data, but rather actively constructing or generating themes through a careful and iterative process of examination and interpretation.

Themes involve a higher level of abstraction and interpretation. They go beyond merely summarizing the data (what participants said) and require the researcher to synthesize codes into meaningful clusters that offer insights into the underlying meaning and significance of the findings in relation to the research question.

Collating codes into potential themes:

The generating initial themes step helps the researcher move from a granular, code-level analysis to a more conceptual, theme-level understanding of the data.

The process of collating codes into potential themes involves grouping codes that share a unifying feature or represent a coherent and meaningful pattern in the data.

The researcher looks for patterns, similarities, and connections among the codes to develop overarching themes that capture the essence of the data.

It’s important to remember that coding is an organic and ongoing process.

You may need to re-read your entire data set to see if you have missed any data relevant to your themes, or if you need to create any new codes or themes.

Once a potential theme is identified, all coded data extracts associated with the codes grouped under that theme are collated. This ensures a comprehensive view of the data pertaining to each theme.

The researcher should ensure that the data extracts within each theme are coherent and meaningful.

This step helps ensure that your themes accurately reflect the data and are not based on your own preconceptions.

By the end of this step, the researcher will have a collection of candidate themes (and maybe sub-themes), along with their associated data extracts.

However, these themes are still provisional and will be refined in the next step of reviewing the themes.

This process is similar to sculpting, where the researcher shapes the “raw” data into a meaningful analysis. This involves grouping codes that share a unifying feature or represent a coherent pattern in the data:

Example: The researcher would gather all the data extracts related to “Financial Obstacles and Support,” such as quotes about struggling to pay for tuition, working long hours, or receiving scholarships.

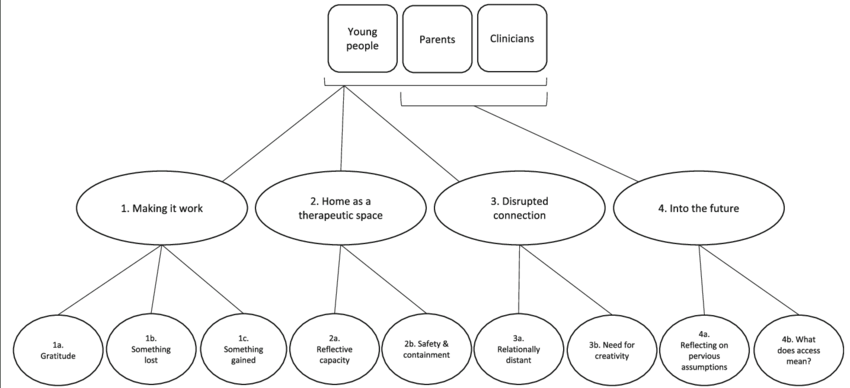

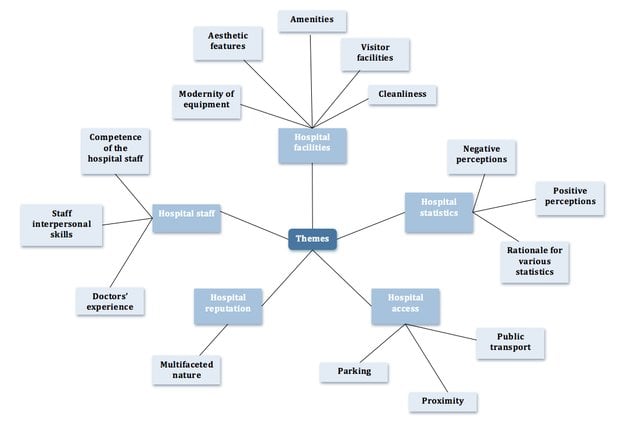

Thematic maps can help visualize the relationship between codes and themes. These visual aids provide a structured representation of the emerging patterns and connections within the data, aiding in understanding the significance of each theme and its contribution to the overall research question.

Thematic maps often use visual elements like boxes, circles, arrows, and lines to represent different codes and themes and to illustrate how they connect to one another.

Thematic maps typically display themes and subthemes in a hierarchical structure, moving from broader, overarching themes to more specific, nuanced subthemes.

Source: Stewart, C., Konstantellou, A., Kassamali, F., McLaughlin, N., Cutinha, D., Bryant-Waugh, R., … & Baudinet, J. (2021). Is this the ‘new normal’? A mixed method investigation of young person, parent and clinician experience of online eating disorder treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic.Journal of eating disorders,9(1), 78.

Maps can help researchers visualize the connections and tensions between different themes, revealing how they intersect or diverge to create a more nuanced understanding of the data.

Similar to the iterative nature of thematic analysis itself, thematic maps are fluid and adaptable, changing as the researcher gains a deeper understanding of the data.

Maps can highlight overlaps between themes or areas where a theme might be too broad or too narrow, prompting the researcher to adjust their analysis accordingly.

Example: Studying first-generation college students, the researcher might notice that the codes “financial challenges,” “working part-time,” and “scholarships” all relate to the broader theme of “Financial Obstacles and Support.”

Two main conceptualizations of a theme exist:Bucket theme (domain summary): This approach identifies a pre-defined area of interest (often from interview questions) and summarizes all data relevant to that area.Storybook theme (shared meaning): This approach focuses on identifying broader patterns of meaning that tell a story about the data. These themes go beyond simply summarizing and involve a greater degree of interpretation from the researcher.

Domain summary themes are organized around a shared topic but not a shared meaning, and often resemble “buckets” into which data is sorted.

A domain summary organizes data around a shared topic but not a shared meaning.

In this approach, themes simply summarize what participants mentioned about a particular topic, without necessarily revealing a unified meaning.

Domain summaries group data extracts around a common topic or area of inquiry, often reflecting the interview questions or predetermined categories.

The emphasis is on collating all relevant data points related to that topic, regardless of whether they share a unifying meaning or concept.

While potentially useful for organizing data, domain summaries often remain at a descriptive level, failing to offer deeper insights into the data’s underlying meanings and implications.

These themes are often underdeveloped and lack a central organizing concept that ties all the different observations together.

A strong theme has a “central organizing concept” that connects all the observations and interpretations within that theme and goes beyond surface-level observations to uncover implicit meanings and assumptions.

A theme should not just be a collection of unrelated observations of a topic. This means going beyond just describing the “surface” of the data and identifying the assumptions, conceptualizations, and ideologies that inform the data’s meaning.

It’s crucial to avoid creating themes that are merely summaries of data domains or directly reflect the interview questions.

Example1: A theme titled “Incidents of homophobia” that merely describes various participant responses about homophobia without delving into deeper interpretations would be a topic summary theme.

Tip: Using interview questions as theme titles without further interpretation or relying on generic social functions (“social conflict”) or structural elements (“economics”) as themes often indicates a lack of shared meaning and thorough theme development. Such themes might lack a clear connection to the specific dataset

Braun and Clarke stress that a theme should offer more than a mere description of the data; it should tell a story about the data.

Instead, themes should represent a deeper level of interpretation, capturing the essence of the data and providing meaningful insights into the research question.

In contrast to domain summaries, shared meaning themes go beyond merely identifying a topic. They are organized around a “central organizing concept” that ties together all the observations and interpretations within that theme.

This central organizing concept represents the researcher’s interpretation of the shared meaning that connects seemingly disparate data points.

They reflect a pattern of shared meaning across different data points, even if those points come from different topics.

Example: The theme “‘There’s always that level of uncertainty’: Compulsory heterosexuality at university” effectively captures the shared experience of fear and uncertainty among LGBT students, connecting various codes related to homophobia and its impact on their lives.

Step 4: Reviewing Themes

The researcher reviews, modifies, and develops the preliminary themes identified in the previous step, transforming them into final, well-developed themes.

This phase involves a recursive process of checking the themes against the coded data extracts and the entire data set to ensure they accurately reflect the meanings evident in the data.

The purpose is to refine the themes, ensuring they are coherent, consistent, and distinctive.

According to Braun and Clarke, a well-developed theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set”.

Revisions at this stage might involve creating new themes, refining existing themes, or discarding themes that do not fit the data. For example, you might realize that two provisional themes actually overlap significantly and decide to merge them into a single, more nuanced theme.

Level One: Reviewing Themes Against Coded Data Extracts

Level Two: Evaluating Themes Against the Entire Data Set

Level Three: Considering relationships between codes, themes, and different levels of themes (sub-themes)

Once you have gathered all the relevant data extracts under each theme, review the themes to ensure they are meaningful and distinct.

This step involves analyzing how different codes combine to form overarching themes and exploring the hierarchical relationship between themes and sub-themes.

Within a theme, there can be different levels of themes, often organized hierarchically as main themes and sub-themes.

Some themes may be more prominent or overarching (main themes), while others may be secondary or subsidiary (sub-themes).

Sub-themes provide a way to add depth and richness to your thematic analysis, but they should be used thoughtfully and strategically. A well-structured analysis might rely primarily on clearly defined main themes, using sub-themes selectively to highlight particularly important nuances within those themes.

Too many sub-themes can create a thin, fragmented analysis and suggest that the analysis hasn’t been developed sufficiently to identify the overarching concepts that tie the data together.

It’s important to note that sub-themes are not a necessary feature of a reflexive TA. You can have a robust analysis with just two to six main themes, especially if you are working with a limited word count

The relationship between codes, sub-themes and main themes can be visualized using a thematic map, diagram, or table.

This map helps researchers review and refine themes, ensuring they are internally consistent (homogeneous) and distinct from other themes (heterogeneous).

Refine the thematic map as you continue to review and analyze the data.

Consider how the themes tell a coherent story about the data and address the research question.

If a theme is too broad or diverse, consider splitting it into separate themes or sub-theme.

Example: The researcher might identify “Academic Challenges” and “Social Adjustment” as other main themes, with sub-themes like “Imposter Syndrome” and “Balancing Work and School” under “Academic Challenges.” They would then consider how these themes relate to each other and contribute to the overall understanding of first-generation college students’ experiences.

Final Questions:

Step 5: Defining and Naming Themes

The themes are finalized when the researcher is satisfied with the theme names and definitions.

Defining themesmeans determining the exact meaning of each theme and understanding how it contributes to understanding the data.

Themes should not be overly broad or try to encompass too much, and should have a singular focus. They should be distinct from one another and not repetitive, although they may build on one another.

In this phase the researcher specifies the essence of each theme.

Naming themesinvolves developing a clear and concise name that effectively conveys the essence of each theme to the reader. A good name for a theme is informative, concise, and catchy.

For example, “‘There’s always that level of uncertainty’: Compulsory heterosexuality at university” is a strong theme name because it captures the theme’s meaning. In contrast, “incidents of homophobia” is a weak theme name because it only states the topic.

For instance, a theme labeled “distrust of experts” might be renamed “distrust of authority” or “conspiracy thinking” after careful consideration of the theme’s meaning and scope.

Step 6: Producing the Report

Braun and Clarke differentiate between two distinct approaches to presenting the analysis in qualitative research: the “establishing the gap model” and the “making the argument model” (p.120).

Establishing the Gap Model:

This model operates on the premise that knowledge gaps exist due to limited research in specific areas or shortcomings in current research.

This approach frames the research’s purpose as filling these identified gaps. Braun and Clarke critique this model as echoing apositivist-empiricist view of researchas a quest for definitive truth, which they argue is incongruent with the nature of qualitative research.

They suggest this approach aligns more with a quantitative perspective that seeks to uncover objective truths.

Making the Argument Model:

Braun and Clarke advocate for the “making the argument model,” particularly in the context of qualitative research.

This model situates the research’s rationale within existing knowledge and theoretical frameworks.

This approach might negate the need for a literature review before data analysis, allowing the research findings to guide the exploration of relevant literature.

Method Section of Thematic Analysis

A well-crafted method section goes beyond a superficial summary of the six phases.

It provides a clear and comprehensive account of the analytical journey, allowing readers to trace the researchers’ thought process, assess the trustworthiness of the findings, and understand the rationale behind the methodological choices made.

This transparency is essential for ensuring therigorand validity of thematic analysis as a qualitative research method.

The method section should explicitly state the type of thematic analysis undertaken and the specific version used (e.g., reflexive thematic analysis, codebook thematic analysis).

It should also explain the rationale for selecting this specific approach in relation to the research questions.

For instance, if a study focuses on exploring participants’ lived experiences, an inductive (reflexive) approach might be more suitable.

Clearly describe the method used to collect data (e.g., interviews,focus groups, surveys, documents).

Specify the size of the data set (e.g., number of interviews, focus groups, or documents) and the characteristics of the participants or texts included.

Braun and Clarke caution against merely listing the six phases of thematic analysis because presenting the phases as a series of steps implies that thematic analysis is a linear and objective process that can be separated from the researcher’s influence.

It should demonstrate an understanding of the principles of reflexivity and transparency.

By embracing reflexivity and transparency, researchers using thematic analysis can move away from a simplistic “recipe” approach and acknowledge the iterative and interpretive nature of qualitative research.

Reflexivityinvolves acknowledging and critically examining how the researcher’s own subjectivity might be shaping the research process.

It requires reflecting on how personal experiences, beliefs, and assumptions could influence the interpretation of data and the development of themes.

For example, a researcher studying experiences of discrimination might reflect on how their own social identities and experiences with prejudice could impact their understanding of the data.

Transparencyinvolves clearly documenting the decisions made throughout the research process.

This includes explaining the rationale behind coding choices, theme development, and the selection of data extracts to illustrate themes.

For example, the researcher(s) might discuss the process of selecting particular data extracts or how their initial interpretations evolved over time.

Transparency allows readers to understand how the findings were generated and to assess thetrustworthiness of the research.

The researcher(s) could provide a detailed account of how they moved from initial codes to broader themes, including examples of how they resolved discrepancies between codes or combined them into overarching categories.

While transparency requires detail and rigor, it should not come at the expense of clarity and accessibility.

Braun and Clarke encourage researchers to write in a clear, engaging style that makes the research process and findings accessible to a wide audience, including those who might not be familiar with qualitative research methods.

Writing About Themes

Athematic analysis reportshould provide a convincing and clear, yet complex story about the data that is situated within a scholarly field.

A balance should be struck between the narrative and the data presented, ensuring that the report convincingly explains the meaning of the data, not just summarizes it.

The report should be written in first-person active tense, unless otherwise stated in the reporting requirements.

Regardless of the presentation style, researchers should aim to “show” what the data reveals and “tell” the reader what it means in order to create a convincing analysis.

Tips

Themes should connect logically and meaningfully and, if relevant, should build on previous themes to tell a coherent story about the data.

Avoid using phrases like “themes emerged” as it suggests that the themes were pre-existing entities in the data, waiting to be discovered. This undermines the active role of the researcher in interpreting and constructing themes from the data.

Data extracts serve as evidence for the themes identified in TA. Without them, the analysis becomes unsubstantiated and potentially unconvincing to the reader.

The report should include vivid, compelling data extracts that clearly illustrate the theme being discussed and should incorporate extracts from different data sources, rather than relying on a single source.

Not all data extracts are equally effective. Choose extracts that vividly and concisely illustrate the theme’s central organizing concept.

Having too few data extracts for a theme weakens the analysis and makes it appear “thin and sketchy”. This may leave the reader unconvinced about the theme’s validity and prevalence within the data.

The analysis should go beyond a simple summary of the participant’s words and instead interpret the meaning of the data.

Data extracts should not be presented without being integrated into the analytic narrative. They should be used to illustrate and support the interpretation of the data, not just reiterate what the participants said.

Researchers should strive to maintain a balance between the amount of narrative and the amount of data presented.

A good thematic analysis strikes a balance between presenting data extracts and providing analytic commentary. A common rule of thumb is to aim for a 50/50 ratio.

A robust thematic analysis acknowledges and explores the full range of data, including those that challenge the dominant patterns.

Ignoring data that doesn’t neatly fit into identified themes is a significant pitfall in thematic analysis.

Failing to acknowledge and explore contradictory data can lead to an incomplete or misleading analysis, potentially obscuring valuable insights.

Embracing contradictions and exploring their potential meanings leads to a more comprehensive and insightful analysis.

Discussion Section

The discussion section should engage critically with the findings, connect them to existing knowledge, and contribute to a deeper understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

Braun and Clarke emphasize that the discussion section should not merely summarize the themes but rather weave a compelling and insightful narrative that connects the analysis back to the research question, existing literature, and broader theoretical discussions.

While each theme should have a distinct focus, the discussion should also draw connections between themes, creating a cohesive and interconnected narrative.

They advocate for a style that engages the reader, convinces them of the validity of the findings, and leaves them with a sense of “so what?” – a clear understanding of the significance and implications of the research.

Potential Pitfalls to Avoid

Reducing Bias

Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis, which they term “reflexive TA,” places the researcher’s subjectivity and reflexivity at the forefront of the research process.

Rather than striving for an illusory objectivity, reflexive TA recognizes and values the researcher’s active role in shaping the research, from data interpretation to theme construction.

When researchers are both reflexive and transparent in their thematic analysis, it strengthens the trustworthiness and rigor of their findings.

The explicit acknowledgement of potential biases and the detailed documentation of the analytical process provide a stronger foundation for the interpretation of the data, making it more likely that the findings reflect the perspectives of the participants rather than the biases of the researcher.

Reflexivity

Reflexivityinvolves critically examining one’s own assumptions and biases, is crucial in qualitative research to ensure the trustworthiness of findings.

It requires acknowledging that researcher subjectivity is inherent in the research process and can influence how data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

Braun and Clarke argue that the researcher’s background, experiences, theoretical commitments, and social position inevitably shape how they approach and make sense of the data.

Reflexivity encourages researchers to explicitly acknowledge their preconceived notions, theoretical leanings, and potential biases.

Reflexivity involves critically examining how these personal and professional experiences influence the research process, particularly during data interpretation and theme development.

Researchers are encouraged to make these influences transparent in their methodology and throughout their analysis, fostering a more honest and nuanced account of the research.

Memosoffer a space for researchers to step back from the data and ask themselves probing questions about their own perspectives and potential biases.

Researchers can ask: How might my background or beliefs be shaping my interpretation of this data? Am I overlooking alternative explanations? Am I imposing my own values or expectations on the participants?

By actively reflecting on how these factors might influence their interpretation of the data, researchers can take steps to mitigate their impact.

This might involve seeking alternative explanations, considering contradictory evidence, or discussing their interpretations with others to gain different perspectives.

Reflexivityis not a one-time activity but an ongoing process that should permeate all stages of the research, from the initial design to the final write-up.

This involves constantly questioning one’s assumptions, interpretations, and reactions to the data, considering alternative perspectives, and remaining open to revising initial understandings.

Braun and Clarke provide a series of probing questions that researchers can ask themselves throughout the analytic process to encourage this reflexivity.

Transparency

Transparency refers to clearly documenting the research process, including coding decisions, theme development, and the rationale behind behind theme development.

Transparency is not merely about documenting what was done but also about clearly articulatingwhyandhowspecific analytic choices were made throughout the research process, from study design to data interpretation.

This transparency allows readers to understand the researchers’ perspectives, the rationale behind their decisions, and the potential influences on the findings, ultimately strengthening thecredibilityand trustworthiness of the research

This transparency helps ensure the trustworthiness and rigor of the findings, allowing other researchers to assess the credibility of the findings and potentially replicate the analysis.

Transparency in Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis is not merely about adhering to a set of reporting guidelines; it’s about embracing an ethos of openness, reflexivity, and accountability throughout the research process.

By illuminating the “messiness” of qualitative research and clearly articulating the researchers’ perspectives and decisions, reflexive TA promotes a more honest, trustworthy, and ultimately, more insightful form of qualitative inquiry.

Transparency requires researchers to provide a clear and detailed account of their analytical choices throughout the research process.

This includes documenting the rationale behind coding decisions, the process of theme development, and any changes made to the analytical approach during the study.

By making these decisions transparent, researchers allow others to scrutinize their work and assess the potential for bias.

Advantages

Disadvantages

Reading List

Examples of Good Practice

Resources

Listen to Victoria Clarke talking on theNEURO_QUALpodcast onUnderstanding and Applying Reflexive Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research– May 2023

![]()

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Saul McLeod, PhD

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.