On This Page:ToggleExperimentCritical EvaluationEthical IssuesLearning Check

On This Page:Toggle

On This Page:

Watson and Rayner (1920) conducted the Little Albert Experiment to answer 3 questions:

Can an infant be conditioned to fear an animal that appears simultaneously with a loud, fear-arousing sound?

Would such fear transfer to other animals or inanimate objects?

How long would such fears persist?

Little Albert Experiment

Ivan Pavlovshowed that classical conditioning applied to animals. Did it also apply to humans? In a famous (though ethically dubious) experiment,John B. Watsonand Rosalie Rayner showed it did.

Conducted at Johns Hopkins University between 1919 and 1920, the Little Albert experiment aimed to provide experimental evidence for classical conditioning of emotional responses in infants

The baseline session occurred when Albert was approximately nine months old to test his reactions to neutral stimuli.

Albert was reportedly unafraid of any of the stimuli he was shown, which consisted of “a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, with [sic] masks with and without hair, cotton wool, burning newspapers, etc.” (Watson & Rayner, 1920, p. 2).

However, what did startle him and cause him to be afraid was if a hammer was struck against a steel bar behind his head. The sudden loud noise would cause “little Albert to burst into tears.

When Little Albert was just over 11 months old, the white rat was presented, and seconds later, the hammer was struck against the steel bar.

After seven pairings of the rat and noise (in two sessions, one week apart), Albert reacted with crying and avoidance when the rat was presented without the loud noise.

By the end of the second conditioning session, when Albert was shown the rat, he reportedly cried and “began to crawl away so rapidly that he was caught with difficulty before reaching the edge of the table” (p. 5). Watson and Rayner interpreted these reactions as evidence of fear conditioning.

By now, little Albert only had to see the rat and immediately showed every sign of fear. He would cry (whether or not the hammer was hit against the steel bar), and he would attempt to crawl away.

Complicating the experiment, however, the second transfer session also included two additional conditioning trials with the rat to “freshen up the reaction” (Watson & Rayner, 1920, p. 9), as well as conditioning trials in which a dog and a rabbit were, for the first time, also paired with the loud noise.

Unlike prior weekly sessions, the final transfer session occurred after a month to test maintained fear. Immediately following the session, Albert and his mother left the hospital, preventing Watson and Rayner from carrying out their original intention of deconditioning the fear they have classically conditioned.

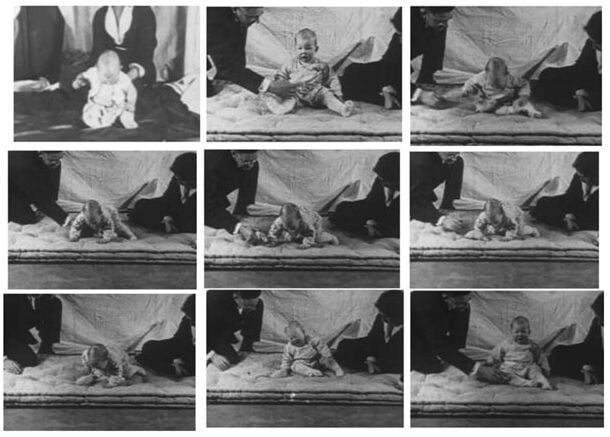

Albert’s reactions to the rat during the baseline session (first still) and transfer session (remaining stills; stills are ordered sequentially by row from top left to lower right). These images are available for use in the public domain.

Albert’s reactions to the rat during the baseline session (first still) and transfer session (remaining stills; stills are ordered sequentially by row from top left to lower right). These images are available for use in the public domain.

Experimental Procedure

Classical Conditioning

Five days later, Watson and Rayner found that Albert developed phobias of objects that shared characteristics with the rat; including the family dog, a fur coat, some cotton wool, and a Sanat mask! This process is known as generalization. The Little Albert Experiment demonstrated that classical conditioning could be used to create a phobia. A phobia is an irrational fear, that is out of proportion to the danger.

Five days later, Watson and Rayner found that Albert developed phobias of objects that shared characteristics with the rat; including the family dog, a fur coat, some cotton wool, and a Sanat mask! This process is known as generalization. The Little Albert Experiment demonstrated that classical conditioning could be used to create a phobia. A phobia is an irrational fear, that is out of proportion to the danger.

Over the next few weeks and months, Little Albert was observed and ten days after conditioning his fear of the rat was much less marked. This dying out of a learned response is called extinction.

Unfortunately, Albert’s mother withdrew him from the experiment the day the last tests were made, and Watson and Rayner were unable to conduct further experiments to reverse the condition response.

Summary:

Critical Evaluation

Methodological Limitations

The study is often cited as evidence that phobias can develop through classical conditioning. However, critics have questioned whether conditioning actually occurred due to methodological flaws (Powell & Schmaltz, 2022).

Other methodological criticisms include:

Theoretical Limitations

The cognitive approach criticizes the behavioral model as it does not take mental processes into account. They argue that the thinking processes that occur between a stimulus and a response are responsible for the feeling component of the response.

Ignoring the role of cognition is problematic, as irrational thinking appears to be a key feature of phobias.

Tomarken et al. (1989) presented a series of slides of snakes and neutral images (e.g., trees) to phobic and non-phobic participants. The phobics tended to overestimate the number of snake images presented.

The Little Albert Film

Powell and Schmaltz (2022) examined film footage of the study for evidence of conditioning. Clips showed Albert’s reactions during baseline and final transfer tests but not the conditioning trials. Analysis of his reactions did not provide strong evidence of conditioning:

Overall, Albert’s reactions seem well within the normal range for an infant and can be readily explained without conditioning. The footage provides little evidence he acquired conditioned fear.

The belief the film shows conditioning may stem from:

Rather than an accurate depiction, the film may have been a promotional device for Watson’s research. He hoped to use it to attract funding for a facility to closely study child development.

This could explain anomalies like the lack of conditioning trials and rearrangement of test clips.

Ethical Issues

Learning Check

References

Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert: A journey to John B. Watson’sinfant laboratory.American Psychologist, 64, 605–614.

Digdon, N., Powell, R. A., & Harris, B. (2014). Little Albert’s alleged neurological persist impairment: Watson, Rayner, and historical revision.History of Psychology,17, 312–324.

Fridlund, A. J., Beck, H. P., Goldie, W. D., & Irons, G. (2012). Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child.History of Psychology,15,1–34.

Griggs, R. A. (2015). Psychology’s lost boy: Will the real Little Albert please stand up?Teaching of Psychology, 42, 14–18.

Harris, B. (1979).Whatever happened to little Albert?. American Psychologist, 34(2), 151.

Harris, B. (2011). Letting go of Little Albert: Disciplinary memory, history, and the uses of myth.Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 47, 1–17.

Harris, B. (2020). Journals, referees and gatekeepers in the dispute over Little Albert, 2009–2014.History of Psychology, 23, 103–121.

Powell, R. A., Digdon, N., Harris, B., & Smithson, C. (2014). Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as “psychology’s lost boy.”American Psychologist, 69, 600–611.

Powell, R. A., & Schmaltz, R. M. (2021). Did Little Albert actually acquire a conditioned fear of furry animals? What the film evidence tells us.History of Psychology,24(2), 164.

Todd, J. T. (1994). What psychology has to say about John B. Watson: Classical behaviorism in psychology textbooks. In J. T. Todd & E. K. Morris (Eds.),Modern perspectives on John B. Watson and classical behaviorism(pp. 74–107). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Tomarken, A. J., Mineka, S., & Cook, M. (1989). Fear-relevant selective associations and covariation bias.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98(4), 381.

Watson, J.B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist Views It.Psychological Review, 20, 158-177.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920).Conditioned emotional reactions.Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1.

Watson, J. B., & Watson, R. R. (1928).Psychological care of infant and child. New York, NY: Norton.

Further Information

![]()

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Saul McLeod, PhD

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.