In recent decades,autismresearch has seen unprecedented growth. The number of published articles on autism has increased tenfold, and funding for autism studieshas expanded significantly.

Despite this surge in research activity, many autistic individuals feel that the outcomes of this research fail to reflect their lived experiences or meaningfully improve their quality of life.

This disconnect highlights a persistent issue in the field:the presence of stigma in autism research.

Stigma in this context refers to negative attitudes, misconceptions, and discriminatory practices that can be embedded in research approaches, methodologies, and interpretations.

To address this critical issue, there is a growing call within the autism community and among progressive researchers to include autistic voices more meaningfully in the research process.

This article explores the problem of stigma in autism research and discusses how the inclusion of autistic perspectives can lead to more respectful, relevant, and impactful studies.

The Problem of Stigma in Autism Research

This approach has led to several problematic outcomes:

Dr. Damian Milton, an autistic academic, describes this problem as the “double empathy problem,” where non-autistic researchers may struggle to fully understand and represent autistic experiences.

As someone who is autistic and also reads and reviews a lot of autism research, I have picked up on some ‘red flags’ that shake my trust.

For example, research that intends to find a way to ‘treat’ autism is a big red flag. As autism is not a disease, it does not need to be cured. A lot of research that attempts to treat autism actually encouragesmasking behaviors, which can actually be detrimental to autistic individuals, such as causingburnoutand a low sense of identity.

Likewise, research that solely focuses on the experiences of autistic individuals from the perspectives of their caregivers or teachers is also questionable. While it can be important to obtain multiple perspectives, excluding autistic perspectives completely without finding a way to communicate with them reduces the accuracy of data.

In general, language that researchers use that stigmatize autism can contribute to the idea that autism is a bad thing.

There have been instances where I have disclosed my autism diagnosis to people, and they have responded in disbelief or as if I have told them I have a terminal illness instead of celebrating that I now understand more about myself.

If autistic individuals are not involved in autism research, this can only perpetuate a lack of understanding and fail to address the real needs of the autism community.

The Value of Autistic Voices in Research

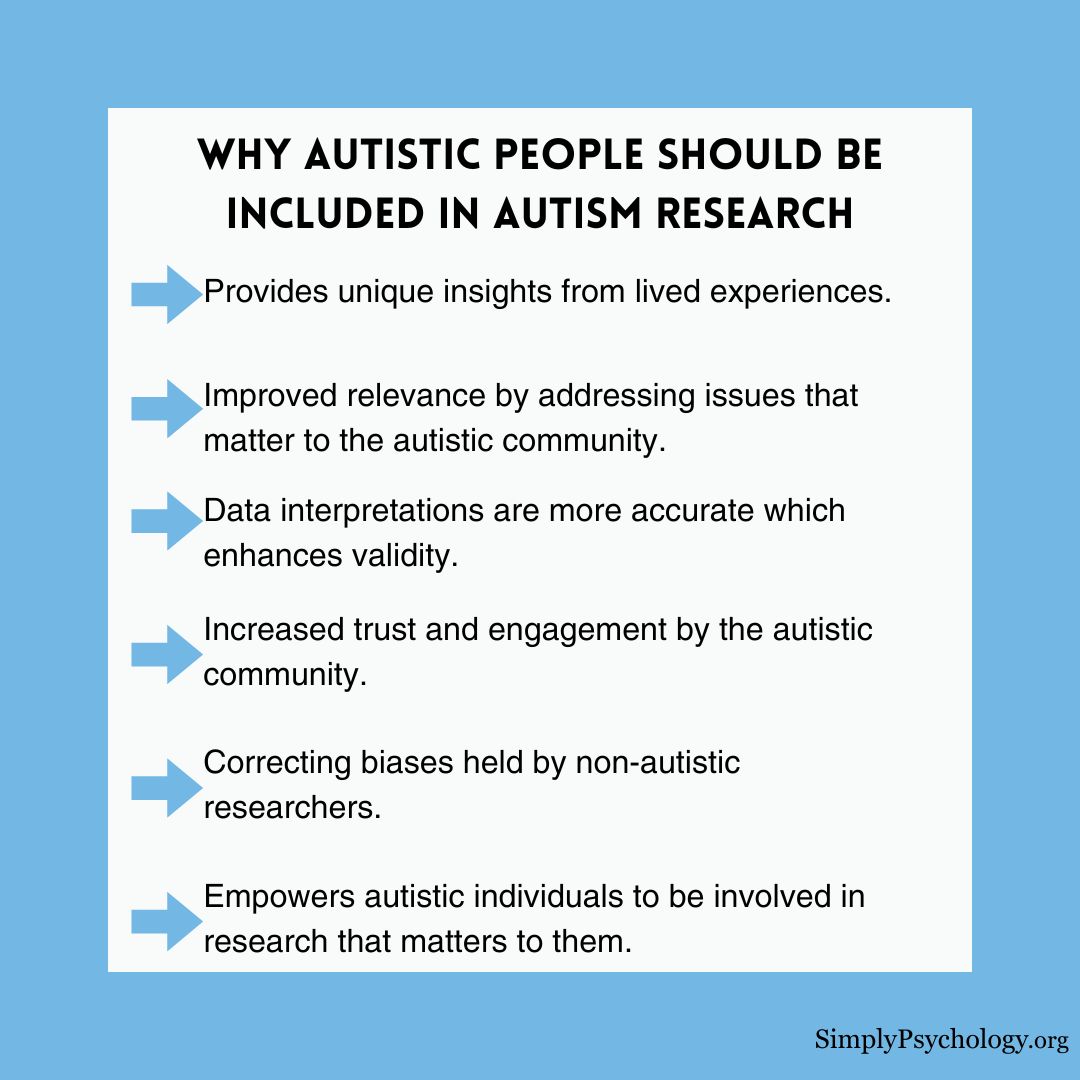

Including autistic perspectives in research brings several crucial benefits that can help combat stigma and improve the quality and relevance of autism studies:

Experiential expertise

Autistic individuals possess unique insights into their own experiences that can inform research questions, methodologies, and interpretations.

Challenging assumptions

Milton(2012) discusses how the “double empathy problem” challenges assumptions about social interaction difficulties in autism, suggesting that communication breakdowns are bidirectional rather than solely due to autistic deficits.

Improved relevance

Enhanced validity

Including autistic perspectives can lead to more accurate interpretations of data and more valid conclusions.

For instance, an autistic researcher might provide insights into why participants responded in certain ways during a study, leading to more nuanced analysis.

Meaningful inclusion of autistic perspectives can lead to numerous other positive outcomes:

Dr. Elizabeth Pellicano, a leading researcher in participatory autism research, emphasizes the importance of this approach: “By spending time with autistic people, without an agenda or specific idea of what the researcher wants to do, we can build research questions on autistic input from the very outset.” (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019)

Strategies for Meaningful Inclusion

To combat stigma and improve research quality, several strategies can be employed to include autistic voices meaningfully:

Co- interview approach

This involved implementing a co-interview procedure for qualitative research, where at least one interviewer is an autistic researcher.

Kaplan-Kahn & Caplan(2023) suggested several benefits for this approach:

The researchers go on to suggest how to implement this approach effectively:

By incorporating these strategies, particularly the co-interview approach, researchers can create more inclusive and effective qualitative studies that better represent autistic experiences and perspectives.

Challenges and Considerations

While inclusion is crucial, it’s not without challenges:

Conclusion

Combating stigma in autism research requires a fundamental shift in how we approach and conduct studies.

By meaningfully including autistic voices at every stage of the research process, we can create more respectful, relevant, and impactful research that truly benefits the autism community.

Researchers, institutions, and funders must commit to this inclusive approach to create a more equitable and effective future for autism research.

As Dr. Sue Fletcher-Watson, a researcher advocating for participatory methods, states: “Nothing about us without us… autistic people should be centered in all conversations regarding autism.”

When evaluating autism research, look for these positive indicators or “green flags”:

By being discerning consumers of autism research, we can collectively promote and support studies that are truly inclusive, relevant, and beneficial to the autistic community.

This shift in awareness can drive meaningful change in how autism research is conducted and applied, ultimately leading to more impactful and respectful outcomes.

References

Crane, L., Adams, F., Harper, G., Welch, J., & Pellicano, E. (2019). ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England.Autism,23(2), 477-493.https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318757048

Fletcher-Watson, S., Adams, J., Brook, K., Charman, T., Crane, L., Cusack, J., … & Pellicano, E. (2019). Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation.Autism,23(4), 943-953.https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786721

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Kapp, S. K., Brooks, P. J., Pickens, J., & Schwartzman, B. (2017). Whose expertise is it? Evidence for autistic adults as critical autism experts.Frontiers in psychology,8, 438.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00438

Kaplan-Kahn, E. A., & Caplan, R. (2023). Combating stigma in autism research through centering autistic voices: A co-interview guide for qualitative research.Frontiers in Psychiatry,14, 1248247.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1248247

Milton, D. E. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem’.Disability & society,27(6), 883-887.https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., Kapp, S. K., Baggs, A., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K., … & Joyce, A. (2019). The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants.Autism,23(8), 2007-2019.https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319830523

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A., & Charman, T. (2014). What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom.Autism,18(7), 756-770.https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314529627

Pellicano, E., Lawson, W., Hall, G., Mahony, J., Lilley, R., Heyworth, M., … & Yudell, M. (2022). “I Knew She’d Get It, and Get Me”: Participants’ Perspectives of a Participatory Autism Research Project.Autism in Adulthood,4(2), 120-129.https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0039

Further information

![]()

Saul McLeod, PhD

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.