On This Page:ToggleWhat is a Scoping Review?Methodological GuidelinesResearch Objective(s)Research ProtocolEligibility CriteriaInformation SourcesSearchingSelecting StudiesData Extraction (Charting)Data SynthesisPresenting ResultsDiscussion & ConclusionPotential ChallengesReading List

On This Page:Toggle

On This Page:

What is a Scoping Review?

A scoping review is a type of research synthesis that maps the existing literature on a broad topic to identify key concepts, research gaps, and types of evidence.

This mapping exercise involves systematically searching for, identifying, and charting relevant literature to understand its characteristics, such as the volume of research, types of studies conducted, key concepts addressed, and prevalent research gaps.

Unlike systematic reviews, which aim to answer specific questions, scoping reviews are exploratory and often used to assess the extent of available evidence and inform future research directions. They involve comprehensive searches and data extraction but do not typically include a detailed synthesis of findings or a critical appraisal of study quality.

When a scoping review methodology would be appropriate:

Scoping reviews can be used as a preliminary step to asystematic review, helping to identify the types of evidence available, potential research questions, and relevant inclusion criteria.

Scoping reviews can help clarify key concepts/definitions in the literature. If a research area has inconsistent terminology or definitions, a scoping review can map out how different concepts are used and potentially propose a unified understanding. This can help refine the focus and scope of a subsequent systematic review.

When not to choose a scoping review methodology:

Scoping reviews help identify areas needing further research, whereas systematic reviews aim to draw conclusions about intervention effectiveness.

Methodological Guidelines

Methodological guidelines aim to improve the consistency and transparency of scoping reviews, enabling researchers to synthesize evidence effectively.

1. Developing review objective(s) & question(s)

A well-defined objective and a set of aligned research questions are crucial for a scoping review’s coherence and direction.

They guide the subsequent steps of the review process, including determining the inclusion and exclusion criteria, developing a search strategy, and guiding data extraction and analysis.

This stage involves a thoughtful and iterative process to ensure that the review’s aims and questions are explicitly stated and closely intertwined.

Defining Objectives:

This step outlines the overarching goals of the scoping review. It explains the rationale behind conducting the review and what the reviewers aim to achieve.

The objective statement should succinctly capture the essence of the review and provide a clear understanding of its purpose.

For instance, a scoping review’s objective might be to map the existing literature on a particular topic and identify knowledge gaps.

Piškur, B., Beurskens, A. J., Jongmans, M. J., Ketelaar, M., Norton, M., Frings, C. A., … & Smeets, R. J. (2012). Parents’ actions, challenges, and needs while enabling participation of children with a physical disability: a scoping review.BMC pediatrics,12, 1-13.

Developing Research Questions:

The research question(s) stem from the objectives and provide a focused roadmap for the review. These questions should be answerable through the scoping review process. The research question(s) should be clear, concise, and directly relevant to the overall objectives.

Using Frameworks:While not mandatory, frameworks can be helpful tools to guide the development of objectives and research questions. Frameworks like PCC (Population, Concept, Context).

How do cultural beliefs and practices (C-context) influence the ways in which parents (P-parents of children with physical disabilities) perceive and address (C-concept) their children’s physical disabilities?

What are the barriers and facilitators (C-concept) to mental health service utilization (C-concept) among veterans (P-population) experiencing homelessness (C-context)?

This scoping review aims to summarize what is known in the African scientific literature (C-context) among cisgender persons (P) about a) individual experiences of GBS within health care settings (C-concept) and b) associations between GBS experiences and health care-related outcomes (C-concept).

What are the main theoretical and methodological characteristics (C-concept) of the current literature (C-context) in the area of stigma and hearing loss and stigma and hearing aids in the elderly population (P-older adults with acquired hearing impairment), and how should future research proceed in expanding this important field of enquiry?

2. Write A Research Protocol

A research protocol is a detailed plan that outlines the methodology to be employed throughout the review process, detailing steps like documenting results, outlining search strategy, and stating the review’s objective

The protocol should be createda priori(before starting the review) to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

While not mandatory, registering your protocol is highly recommended, e.g.FigShareandOpen Science Framework(OSF).

Some journals, such as theJournal of Advanced Nursing,Systematic Reviews,BMC Medical Research Methodology,BMJ Open, andJBI Evidence Synthesis, accept scoping review protocols for publication.

It’s important to note that PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews, does not currently accept scoping review protocols for registration.

Registering a scoping review protocol is highly recommended, even if not mandatory, as it promotes transparency, reduces duplication of effort, and helps to prevent publication bias

Example Protocols:

Tricco, A. C., Zarin, W., Lillie, E., Pham, B., & Straus, S. E. (2017). Utility of social media and crowd-sourced data for pharmacovigilance: a scoping review protocol.BMJ open,7(1), e013474.

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., … & Straus, S. E. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews.BMC medical research methodology,16, 1-10.

3. Developing eligibility criteria

This step involves developing and aligning the inclusion criteria with the objective(s) and question(s).

By providing transparent and well-justified eligibility criteria, researchers can ensure the replicability of their scoping review and allow readers to assess the relevance and appropriateness of the included sources.

When reporting eligibility criteria, emphasize the importance of clarity, justification, and a clear link to the review’s objectives.

By using the PCC framework, researchers can systematically establish boundaries for their scoping review, ensuring that the included sources are relevant to the research question. The framework helps to ensure that the eligibility criteria are comprehensive and well-defined, enabling a more focused and meaningful synthesis of the literature

The initial set of eligibility criteria outlined in the protocol may be subject to adjustments based on the type and volume of studies identified in the initial searches.

David, D., & Werner, P. (2016). Stigma regarding hearing loss and hearing aids: A scoping review.Stigma and Health,1(2), 59.

“An extensive search was conducted to locate peer-reviewed articles that addressed questions related to parent involvement in organized youth sport. To guide article retrieval, two inclusion criteria were used. First, articles were required to highlight some form of parent involvement in organized youth sport. In the present study, organized youth sport was operationalized as “adultorganized and controlled athletic programs for young people,” wherein “participants are formally organized [and] attend practices and scheduled competitions under the supervision of an adult leader” (Smoll & Smith, 2002, p. xi). In line with this criterion, we did not include physical activity, exercise, physical education, and free play settings, which comprise a substantial volume of research in sport and exercise psychology. We also excluded research that simply collected data on parents or from parents but did not explicitly assess their involvement in their children’s sport participation. Second, articles were required to have been published in peer-reviewed, Englishlanguage, academic journals. As such, we did not include books, chapters, reviews, conceptual papers, conference proceedings, theses and (Jones, 2004) dissertations, or organizational “white papers” in this scoping review.”

Dorsch, T. E., Wright, E., Eckardt, V. C., Elliott, S., Thrower, S. N., & Knight, C. J. (2021). A history of parent involvement in organized youth sport: A scoping review.Sport, Exercise, and performance psychology,10(4), 536.

“…to be included in the review, papers needed to measure or focus on specific dimensions of treatment burden, developed in the conceptual framework (e.g. financial, medication, administrative, lifestyle, healthcare and time/travel). Peer-reviewed journal papers were included if they were: published between the period of 2000–2016, written in English, involved human participants and described a measure for burden of treatment, e.g. including single measurements, measuring and/or incorporating one or two dimensions of burden of treatment. Quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method studies were included in order to consider different aspects of measuring treatment burden. Papers were excluded if they did not fit into the conceptual framework of the study, focused on a communicable chronic condition, for example human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) or substance abuse. Papers talking about carer burden, in addition to patient burden of treatment, were also included.”

Sav, A., Salehi, A., Mair, F. S., & McMillan, S. S. (2017). Measuring the burden of treatment for chronic disease: implications of a scoping review of the literature.BMC medical research methodology,17, 1-14.

4. Information Sources

Scoping reviews aim to identify a broad range of relevant studies, including both published and unpublished literature, to provide a comprehensive overview of the topic.

The goal is to be inclusive rather than exhaustive,which differentiates scoping reviews from systematic reviewsthat seek to collate all empirical evidence fitting pre-specified criteria to answer specific research questions.

Information sources for scoping reviews can include a wide range of resources like scholarly databases, unpublished literature, conference papers, books, and even expert consultations.

Report who developed and executed the search strategy, such as an information specialist or librarian. Mention if the search strategy was peer-reviewed using thePeer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist.

Cardoso, R., Zarin, W., Nincic, V., Barber, S. L., Gulmezoglu, A. M., Wilson, C., … & Tricco, A. C. (2017). Evaluative reports on medical malpractice policies in obstetrics: a rapid scoping review.Systematic reviews,6, 1-11.

5. Searching for the evidence

Scoping reviews typically start with a broader, more inclusive search strategy. The initial search is intentionally wide-ranging to capture the breadth of available literature on the topic

To balance breadth and depth in your initial search strategy for a scoping review, consider the following tips based on the gathered search results:

Abela, D., Patlamazoglou, L., & Lea, S. (2024). The resistance of transgender and gender expansive people: A scoping review.Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity.

Search strategy can also be reported in the appendix. For example:Supplementary A: Search strategy for scoping review.

Citation Chasing Process

Citation chasing involves reviewing the reference lists of included studies and examining articles that cite those studies to identify additional relevant literature. This process helps ensure that you capture a comprehensive view of the research landscape.

If citation chasing leads to the identification of new keywords or concepts, document these adjustments and how they were incorporated into the overall search strategy.

6. Selecting the evidence

While articles included in a scoping review are selected systematically, it is important to acknowledge that there is no assumption that the evidence reviewed is exhaustive. This is often due to limitations in the search strategy or difficulty locating specific types of sources.

The goal is to identify relevant studies, with less emphasis on methodological quality. Scoping reviews generally do not appraise the quality of included studies.

Instead, scoping reviews prioritize mapping the existing literature and identifying gaps in research, regardless of the quality of the individual studies.

Two reviewers should independently screen titles and abstracts, removing duplicates and irrelevant studies based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Duffett, M., Choong, K., Hartling, L., Menon, K., Thabane, L., & Cook, D. J. (2013). Randomized controlled trials in pediatric critical care: a scoping review.Critical care,17, 1-9.

7. Extracting the evidence

Charting, also known as data extraction, is a crucial stage in conducting a scoping review.

This process involves systematically collecting relevant information from the sources included in the review using a structured form. It is considered best practice to have at least two reviewers independently extract data from each source

Data charting in scoping reviews differs from data extraction in systematic reviews. While systematic reviews aim to synthesize the results and assess the quality of individual studies, scoping reviews focus on mapping the existing literature and identifying key concepts, themes, and gaps in the research.

Therefore, the data charting process in scoping reviews is typically broader in scope and may involve collecting a wider range of data items compared to the more focused data extraction process used in systematic reviews.

This process goes beyond simply extracting data; it involves characterizing and summarizing research evidence, which ultimately helps identify research gaps.

Lenzen, S. A., Daniëls, R., van Bokhoven, M. A., van der Weijden, T., & Beurskens, A. (2017). Disentangling self-management goal setting and action planning: A scoping review.PloS one,12(11), e0188822.

Constand, M. K., MacDermid, J. C., Dal Bello-Haas, V., & Law, M. (2014). Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare.BMC health services research,14, 1-9.

Data Items

The final charting form, which clearly defines each item, should be included in the scoping review as an appendix or supplementary file, if possible.

“We abstracted data on article characteristics (e.g., country of origin, funder), engagement characteristics and contextual factors (e.g., type of knowledge user, country income level, type of engagement activity, frequency and intensity of engagement, use of a framework to inform the intervention), barriers and facilitators to engagement, and results of any formal assessment of engagement (e.g., attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, benefits, unintended consequences).”

Tricco, A. C., Zarin, W., Rios, P., Nincic, V., Khan, P. A., Ghassemi, M., … & Langlois, E. V. (2018). Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: a scoping review.Implementation Science,13, 1-19.

8. Analyzing the evidence

The key element of a scoping review is the synthesis: that is the process that brings together the findings from the set of included studies in order to draw conclusions based on the body of evidence.

Data synthesis in a scoping review involves collating, combining, and summarizing findings from the included studies.

The data synthesis will be presented in theresults sectionof the scoping review.

Scoping reviews often use a more descriptive approach to synthesis, summarizing the types of evidence available, key findings, and research gaps.

Remember, the goal in a scoping review is not to critically appraise the quality of individual studies or to provide a definitive answer to a narrow research question.

Instead, the synthesis aims to provide a broad overview of the field, mapping out the existing literature and identifying areas for further research.

This descriptive approach allows for a comprehensive understanding of the landscape of a particular research area.

Hutchinson, J., Prady, S. L., Smith, M. A., White, P. C., & Graham, H. M. (2015). A scoping review of observational studies examining relationships between environmental behaviors and health behaviors.International journal of environmental research and public health,12(5), 4833-4858.

9. Presenting the results

The findings should be presented in a clear and logical way that answers the research question(s). This section might include tables, figures, or narrative summaries to illustrate the data.

Narrative Summaries

Write a clear, concise narrative that brings together all of these elements. This should provide readers with a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge in the field, highlighting both what is known and what remains to be explored.

The primary goal of a narrative summary is to weave together the information extracted from multiple sources into a cohesive and understandable narrative. This story should focus on why a specific action is necessary, should be discontinued, or lacks sufficient evidence to determine its efficacy

A well-crafted narrative summary often utilizes headings and subheadings to organize the synthesized information logically.

This approach makes it easier for readers to follow the thought process and understand the relationships between different pieces of evidence.

Strategies on how to be sensitive to patient needs were primarily discussed in the qualitative research articles included in this review. Such strategies included acknowledging and adapting to unique patient identifiers [19,24,25]. For example, clinicians are urged to observe and reflect on fluctuating levels of patient alertness, patient comfort levels in the presence or absence of family members, and different communication barriers such as hearing loss, in order to facilitate clinical interactions [15,19,22]. Of the articles reviewed, 58% identified that careful observation of unique patient characteristics is necessary to providing care that will lead to optimal patient receptiveness and positive health outcomes.

Tables

While narrative summaries primarily use text, incorporating tables, charts, or diagrams can enhance clarity, particularly when presenting complex data patterns.

However, always accompany these visual aids with a clear textual explanation to ensure comprehensive understanding.

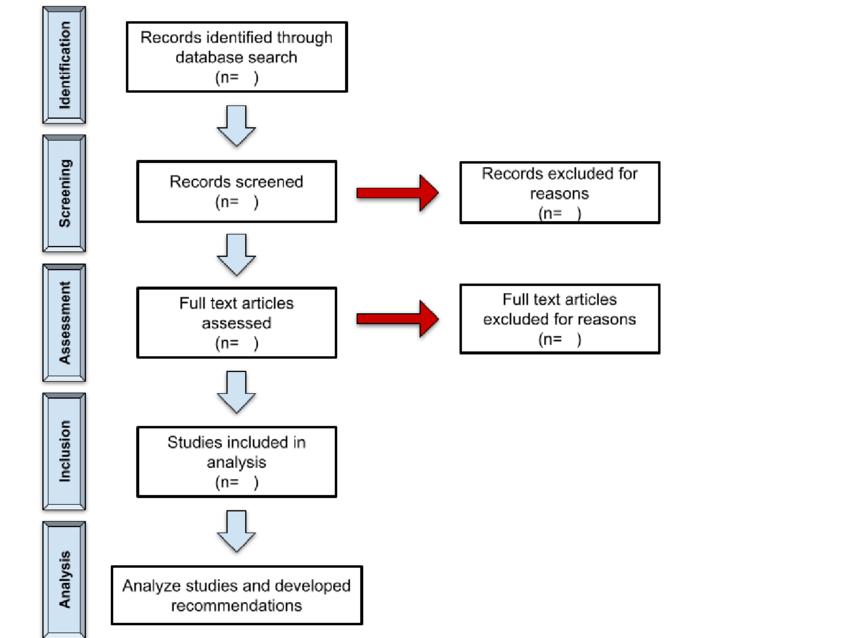

PRISMA Flowchart

Using aPRISMA flowchartin a scoping review is considered good practice. It promotes transparency and allows for a clear understanding of how sources were selected.

Selection of studies according to PRISMA-ScR protocol.

10. Discussion Section And Conclusion

Summarizing the evidence in relation to the purpose of the review, making conclusions and noting any implications of the findings.

It is also essential to remember that scoping reviews, unlike systematic reviews, do not aim to provide concrete recommendations for practice or policy.

Their primary function is to map the existing evidence, identify knowledge gaps, and clarify concepts, rather than synthesize results for direct application in clinical or policy settings

Summarizing the Evidence

“In this scoping review we identified 88 primary studies addressing dissemination and implementation research across various settings of dementia care published between 1998 and 2015. Our findings indicate a paucity of research focusing specifically on dissemination of knowledge within dementia care and a limited number of studies on implementation in this area. We also found that training and educating professionals, developing stakeholder interrelationships, and using evaluative and iterative strategies are frequently employed to introduce and promote change in practice. However, although important and feasible, these strategies only partly address what is repeatedly highlighted in the evidence base: that organisational factors are reported as the main barrier to implementation of knowledge within dementia care. Moreover, included studies clearly support an increased effort to improve the quality of dementia care provided in residential settings in the last decade.”

Lourida, I., Abbott, R. A., Rogers, M., Lang, I. A., Stein, K., Kent, B., & Thompson Coon, J. (2017). Dissemination and implementation research in dementia care: a systematic scoping review and evidence map.BMC geriatrics,17, 1-12.

Limitations

When considering the limitations of a review process, particularly scoping reviews, it’s essential to acknowledge that the goal is breadth, not depth, of information.

“Our scoping review has some limitations. To make our review more feasible, we were only able to include a random sample of rapid reviews from websites of rapid review producers. Further adding to this issue is that many rapid reviews contain proprietary information and are not publicly available. As such, our results are only likely generalizable to rapid reviews that are publicly available. Furthermore, this scoping review was an enormous undertaking and our results are only up to date as of May 2013.”

Tricco, A. C., Antony, J., Zarin, W., Strifler, L., Ghassemi, M., Ivory, J., … & Straus, S. E. (2015). A scoping review of rapid review methods.BMC medicine,13, 1-15.

Conclusions

“The lack of evidence to support physiotherapy interventions for this population appears to pose a challenge to physiotherapists. The aim of this scoping review was to identify gaps in the literature which may guide a future systematic review. However, the lack of evidence found means that undertaking a systematic review is not appropriate or necessary […]. This advocates high quality research being needed to determine what physiotherapy techniques may be of benefit for this population and to help guide physiotherapists as how to deliver this.”

Hall, A. J., Lang, I. A., Endacott, R., Hall, A., & Goodwin, V. A. (2017). Physiotherapy interventions for people with dementia and a hip fracture—a scoping review of the literature.Physiotherapy,103(4), 361-368.

Potential Challenges

Reading List

![]()

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Saul McLeod, PhD

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.