On This Page:ToggleFunctionsLocationStructureDamage

On This Page:Toggle

On This Page:

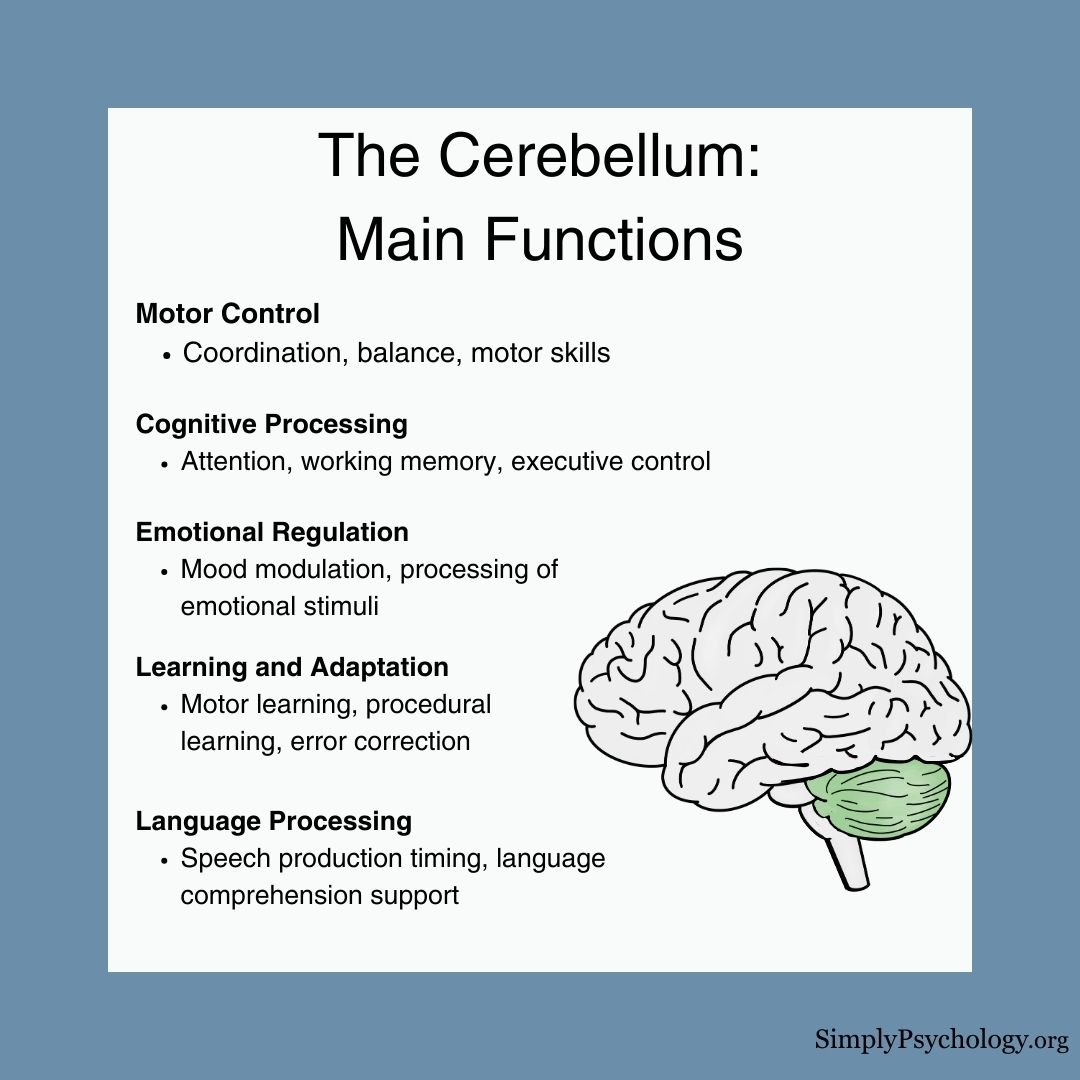

The cerebellum, which stands for ‘little brain,’ is ahindbrain structurethat controls balance, coordination, movement, and motor skills, and it is thought to be important in processing some types of memory.

In psychology, the cerebellum is often defined as a brain region responsible for coordinating and refining motor movements, ensuring balance and posture, and facilitatingprocedural learning.

While traditionally associated primarily with motor control, recent research has expanded our understanding of the cerebellum’s role, suggesting its involvement in cognitive processes,emotion regulation,working memory, attention, and even some aspects of language processing.

Thus, in a psychological context, the cerebellum is related to the physical coordination of movements and the coordination of thoughts and emotions.

The cerebellum is also one of the few mammalian brain structures where adultneurogenesis(the development of new neurons) has been confirmed (Ponti, Peretto & Bonfanti, 2008).

Cerebellum functions

The cerebellum, situated at the base of the brain, plays a crucial role in both motor and cognitive functions.

While traditionally associated with motor coordination, balance, and fine-tuning of movements, research over the past few decades has revealed its significant involvement in higher cognitive processes (Buckner, 2013).

The cerebellum receives sensory information about body position and intended movements from various brain areas, allowing it to coordinate smooth, precise actions without conscious awareness (Buckner, 2013).

It integrates this information to organize muscle group actions, including eye movements.

In motor learning, the cerebellum is vital for acquiring new skills. For example, when learning to ride a bike, the cerebellum helps fine-tune motor skills until the action becomes seamless and automatic.

Recent research suggests that the majority of the human cerebellum maps onto cerebral networks involved in cognitive rather than motor functions (Buckner et al., 2013).

This expanded understanding opens new avenues for exploring the cerebellum’s role in various neurological and psychiatric conditions, including (but not limited to):

ADHD

Studies have found alterations in cerebellar white matter tracts in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), particularly reduced microstructural organization in the middle cerebellar peduncle.

These structural differences correlate withADHD symptoms, especially hyperactivity levels, suggesting the cerebellum may contribute to attention and cognitive symptoms in ADHD (Parkkinen et al., 2024).

It makes sense that the cerebellum plays a role in ADHD since the cognitive functions associated with the cerebellum (e.g., attention and working memory) are also key areas of difference in this disorder.

Autism

Studies suggest a link between cerebellum differences andautism.

Animal studies have shown that disrupting cerebellar circuits, especially involving Purkinje cells, can lead to autism-like behaviors including social difficulties and repetitive behaviors. Abnormal cerebellar-cerebral connectivity is also observed in autistic individuals (van der Heijden et al., 2021).

However, a comprehensive study of over 400 individuals found no significant differences in cerebellar anatomy between autism and control groups, even when accounting for factors like age, IQ, and symptom severity (Laidi et al., 2022).

This doesn’t rule out more subtle or functional differences but suggests that anatomical cerebellar alterations may not be a defining feature of autism.

Anxiety Disorders

Some research suggests cerebellar involvement inanxiety disorders.

Studies have found that lesioning the cerebellum in animal models can prevent avoidance responses to anxiety-provoking situations (Caulfield & Servatius, 2013).

Additionally, cerebellar hyperactivity has been correlated with increased arousal in conditions like PTSD andgeneralized anxiety disorder(Abadie et al.,1999; Critchley et al., 2000).

Schizophrenia

The cerebellum’s role in cognitive and emotional processing has led to investigations of its involvement in various other conditions including schizophrenia.

Brain imaging studies have found that there are reduced sizes of the cerebellum in patients who are diagnosed with schizophrenia (Nopoulos et al., 1999).

There is also evidence from neuroimaging that patients with schizophrenia have less blood flow to the cerebellar cortex during the performance of cognitive tasks, such as attention and tasks that involve using short-term and working memory (Crespo-Facorro et al., 2007).

This expanded view of cerebellar function emphasizes its importance not only in motor control but also in cognitive and emotional processes, highlighting its potential relevance in understanding and treating a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Where Is It Located?

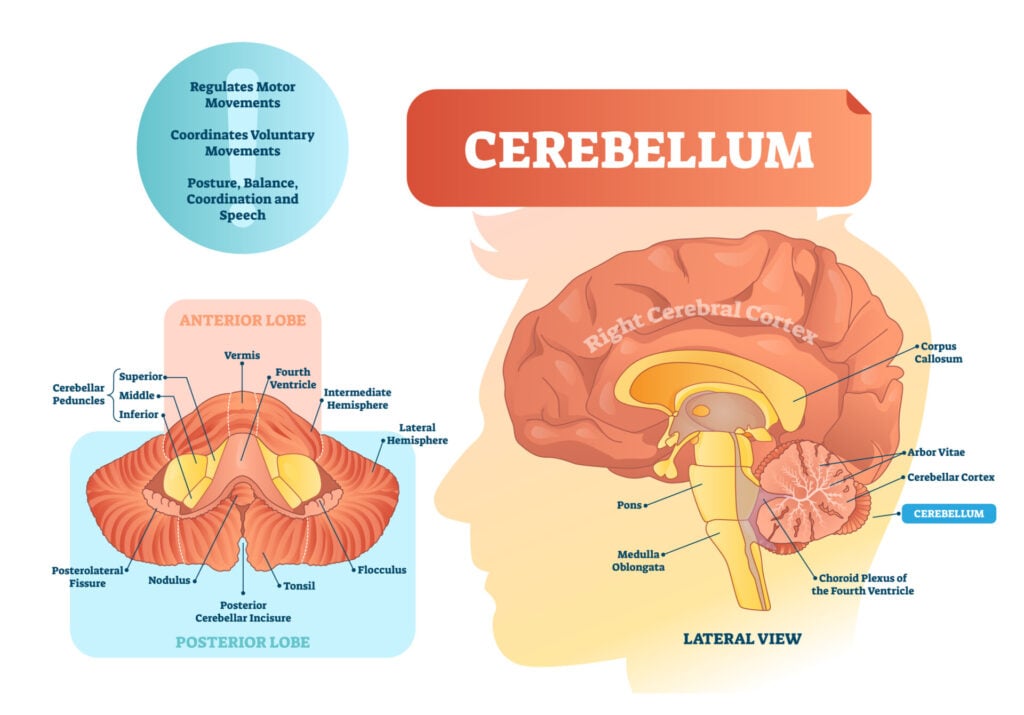

The cerebellum is located at the back of the brain, behind the brainstem, below the temporal andoccipital lobes, and beneath the back of the cerebrum.The cerebellum is also divided into two hemispheres, like the cerebral cortex. Unlike the cerebral hemispheres, each hemisphere of the cerebellum is associated with each side of the body.

The cerebellum is located at the back of the brain, behind the brainstem, below the temporal andoccipital lobes, and beneath the back of the cerebrum.

The cerebellum is also divided into two hemispheres, like the cerebral cortex. Unlike the cerebral hemispheres, each hemisphere of the cerebellum is associated with each side of the body.

Structure

The cerebellum consists of thecerebellar cortex, the outer layer, containing folder brain tissue, filled with most of the cerebellum’s neurons. It plays a key role in processing and integrating information sent to the cerebellum.

There is also a fluid-filled ventricle andcerebellar nuclei, which is the innermost part, containingneurons that communicate informationfrom the cerebellum to other areas of the brain.

The cerebellum can also be divided into three functional areas:

Damage

Cerebellar damage results in the breakdown and destruction of nerve cells which can have long-lasting effects. A person who has damage to their cerebellum may experience some of the following symptoms:

Drinking alcohol has an immediate and temporary effect on the cerebellum as the body’s coordination and movements become clumsy.

Someone who is intoxicated with alcohol may not be able to walk in a straight line and lose their balance.

Although these symptoms are temporary, repeated alcohol misuse, becoming an alcohol use disorder, can have long-lasting impacts on the cerebellum and lead to these symptoms being more long-lasting.

Other causes of damage to the cerebellum can come from injury to the head, such as falling backward and hitting the back of the head where the cerebellum lies.

Brain tumors and infections in the brain can also cause long-lasting damage to the cerebellum.

Damage could also occur through medical issues such as having Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and experiencing a stroke.

Similarly, lead or mercury poisoning and the overuse of certain medications (e.g., benzodiazepines) can also cause lasting damage to cerebellar function.

Summary

There is growing research and data to suggest that the cerebellum plays a role, not only in controlling balance and voluntary movement, but also in the control of cognitive and emotional processes.

There is also evidence through neuroimaging studies to suggest the cerebellum’s involvement in neurological disorders.

In order to preserve the health of the cerebellum, limiting or stopping smoking and drinking alcohol is a suggestion. This is because they both contribute to raising blood pressure which could ultimately lead to a stroke.

Exercising more and eating a healthy diet both help lower blood pressure, and thus, the risk of a stroke, so this is encouraged to protect the cerebellum.

Finally, protecting the head in general, such as wearing helmets when cycling, wearing seatbelts in the car, and taking care to prevent falls in the home, can limit the risk of damage to this area of the brain.

References

Abadie, P., Boulenger, J. P., Benali, K., Barre, L., Zarifian, E., & Baron, J. C. (1999). Relationships between trait and state anxiety and the central benzodiazepine receptor: a PET study.European Journal of Neuroscience, 11(4), 1470-1478.

Buckner, R. L. (2013). The cerebellum and cognitive function: 25 years of insight from anatomy and neuroimaging.Neuron,80(3), 807-815.

Caulfield, M. D., & Servatius, R. J. (2013). Focusing on the possible role of the cerebellum in anxiety disorders. New Insights into Anxiety Disorders (Durbano F, Ed.).InTech, Rijeka, HR, 41-70.

Crespo-Facorro, B., Barbadillo, L., Pelayo-Terán, J. M., & Rodríguez-Sánchez, J. M. (2007). Neuropsychological functioning and brain structure in schizophrenia.International Review of Psychiatry, 19(4), 325-336.

Critchley, H. D., Corfield, D. R., Chandler, M. P., Mathias, C. J., & Dolan, R. J. (2000). Cerebral correlates of autonomic cardiovascular arousal: a functional neuroimaging investigation in humans. The Journal of physiology, 523(1), 259-270.

Gowen, E., & Miall, R. C. (2007). The cerebellum and motor dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders. The Cerebellum, 6(3), 268-279.

Laidi, C., Floris, D. L., Tillmann, J., Elandaloussi, Y., Zabihi, M., Charman, T., … & Simonoff, E. (2022). Cerebellar atypicalities in autism?.Biological psychiatry,92(8), 674-682.

Nopoulos, P. C., Ceilley, J. W., Gailis, E. A., & Andreasen, N. C. (1999). An MRI study of cerebellar vermis morphology in patients with schizophrenia: evidence in support of the cognitive dysmetria concept.Biological psychiatry, 46(5), 703-711.

Parkkinen, S., Radua, J., Andrews, D. S., Murphy, D., Dell’Acqua, F., & Parlatini, V. (2024). Cerebellar network alterations in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience,49(4), E233-E241.

Phillips, J. R., Hewedi, D. H., Eissa, A. M., & Moustafa, A. A. (2015). The cerebellum and psychiatric disorders.Frontiers in public health, 3, 66.

Ponti, G., Peretto, P., & Bonfanti, L. (2008). Genesis of neuronal and glial progenitors in the cerebellar cortex of peripuberal and adult rabbits.PLoS One, 3(6), e2366.

Stoodley, C. J. (2016). The cerebellum and neurodevelopmental disorders.The Cerebellum, 15(1), 34-37.

Further InformationKniermin J. Neuroscience online: an electronic textbook for the neurosciences. Chapter 5: Cerebellum. University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.Stoodley, C. J. (2016). The cerebellum and neurodevelopmental disorders. The Cerebellum, 15(1), 34-37.D”Angelo, E. (2019). The cerebellum gets social. Science, 363(6424), 229-229.

Further Information

Kniermin J. Neuroscience online: an electronic textbook for the neurosciences. Chapter 5: Cerebellum. University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.Stoodley, C. J. (2016). The cerebellum and neurodevelopmental disorders. The Cerebellum, 15(1), 34-37.D”Angelo, E. (2019). The cerebellum gets social. Science, 363(6424), 229-229.

Kniermin J. Neuroscience online: an electronic textbook for the neurosciences. Chapter 5: Cerebellum. University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Stoodley, C. J. (2016). The cerebellum and neurodevelopmental disorders. The Cerebellum, 15(1), 34-37.

D”Angelo, E. (2019). The cerebellum gets social. Science, 363(6424), 229-229.

![]()

Saul McLeod, PhD

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.